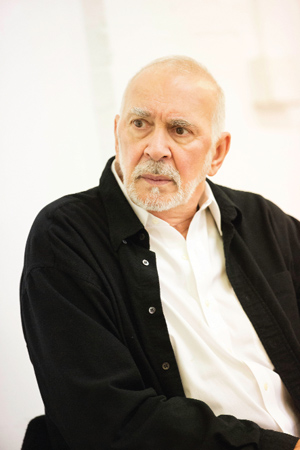

Frank Langella interview

Broadway Royal

Broadway & Hollywood star Frank Langella talks to Latest 7 as he prepares to play King Lear at Chichester’s Minerva Theatre

As commanding a presence offstage as he is on stage, actor Frank Langella’s long, lean frame seems almost incongruous in one of the temporary portable cabins to which Chichester’s staff have been relocated during the Festival Theatre’s ambitious re-development. Langella, a relatively rare visitor to these shores, at least for professional reasons, has come to West Sussex to play the title role in Shakespeare’s King Lear, a role that places great demands on the actor, physically, vocally and emotionally. Now in his mid-70s but looking much younger, Langella’s initial response to Chichester’s offer was not exactly encouraging.

“I said ‘No No No’ – three times ‘No’,” he recalls with a smile. “Then I made the great decision to read the play, which I hadn’t done for more than 20 years. I realised that now I’ve reached 75, I get what Lear is going through and I saw that the journey he takes during the course of the play is so much more interesting than I’d supposed. Once I’d decided to do it, I looked at every performance of Lear I could find to see what I could steal.”

Is King Lear a favourite play of Langella’s?

“It has the reputation of being a play that is impossible to do,” he replies. “I’d compare it to a series of 12 one-act plays. It’s as if Shakespeare had been writing King Lear one afternoon and he’d left the pages outside: the wind had scattered them and he’d been unable to put them back in the right order.”

Langella is inclined to keep his ideas about Lear to himself, at least at this stage of the production.

“I’m always loath to talk about my take on the character. I don’t want the audience to know in advance what I’ve decided. I can see members of the public telling their friends that I’d be playing Lear as a Spartan general or something because of what I said in a newspaper interview. I will say, however, that finding the central core of Lear, exploring why he does what he does, has been my main concern. He takes off his crown because he doesn’t want the responsibility yet he still wants everybody to continue to treat him as before. How he reacts to this contradiction is revealing. He doesn’t say that he wants to be king again. Instead, he begins to understand things which he has never thought about before.”

Lear is said to be one of the most taxing roles in world drama. How has Langella been finding rehearsals?

“Everything about Lear is very powerful and emotional but at least Shakespeare gives Lear a 45- minute respite in the middle of the play. But Part One of the play is an enormous mountain to climb. You have to be in good health to play a part of the size of Lear and you have to keep your wits about you. And you need passion. If you don’t have passion, you shouldn’t play any part including King Lear.”

While he points out that The Bard does not really occupy the central position in the American theatre which he is granted on this side of the Atlantic, Langella has had plenty of experience of acting Shakespeare in the United States.

“I’ve played Malvolio, Prospero, Iago, Richard III, Malcolm in the Scottish Play and Theseus in A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” he points out. “As a young man I was more drawn to Chekhov, to Shaw, to some Miller and to Tennessee Williams. Shakespeare isn’t really part of the American tradition as he is in this country, although I have the impression that there’s more Shakespeare being produced in the States at the moment than for some time.”

With three Tony Awards under his belt, Langella is one of America’s most acclaimed stage actors. Yet it is interesting to note that the recognition has been made for plays and characters a little outside the mainstream of the American theatre; Albee’s Seascape, Turgenev’s Fortune’s Fool and the ex-President in Peter Morgan’s Frost/Nixon. How does he explain this apparent paradox?

“Look at me,” he exclaims. “I’m not a regular guy like Willy Loman in Death Of A Salesman although I did once play Rodolfo in Miller’s A View from the Bridge. I don’t have that street look about me. Besides, I was also more drawn to epic characters in pieces by European writers.”

As Langella remarks, he’s seldom been cast as an ordinary Joe. There is an exoticism about him which must have contributed to the success he enjoyed in playing Dracula on both stage and screen. You wonder how an actor begins to play such a role, a creature that is the stuff of nightmares rather than a fully-rounded character.

“You don’t play him as a vampire, you play him as a man with a unique problem,” explains Langella. “In the way that some men can be addicted to cigarettes or violence or alcohol, Dracula needs blood. Everybody adjusts to what their particular addiction might be and how do people handle their addictions, anyway? I never saw Dracula as anything but a flawed man.”

Langella has played a number of figures whose behaviour and personality could be described as morally dubious. But he insists that it is not his job to pass judgement on the man he is playing.

“Once I decide to take on a particular part, I fall in love with the character. You have to look at the world through the character’s eyes. Lear says to his daughters – I was a great father to you – even though he wasn’t. But he believes it to be true.”

Langella has latterly received enormous acclaim for his performance as the disgraced ex-President Nixon, a performance which won him not only his third Tony but also an Oscar nomination. For many left-leaning people in America, Richard Nixon, though no bloodsucker, had something of Dracula’s night-haunting menace.

“I grew up in the 1950s and 1960s; I saw his resignation on live television. For many of us, Nixon was the enemy. But when you play a real person, I believe you have an extra responsibility to look at things from his point of view and most reviewers understood what I was trying to do. One of Nixon’s grand-daughters came round after a performance. She took my hand and thanked me for making her grandfather a human being.”

Twice a year, Langella distils the fruits of his 53 years on the stage and passes on his accumulated wisdom in a series of masterclasses.

“I never had a mentor and I was drawn more to writers rather than actors. I didn’t have a role model and in a way, I taught myself acting. I learnt in the field, as it were. I learnt that the audience are your teachers. I’m sure that we’ll learn more from the first preview than anything we discovered in rehearsal. I find teaching immensely enjoyable. I get a lot of pleasure from helping young actors unlock the key to a speech or a character.”

While he has no plans to retire officially, Langella hints that he may discreetly stand down.

“If I find that I don’t have the breath or the energy, I’ll simply stop.” Langella predicts. “I became an actor because I wanted to express myself and at the age of seven, when the teacher asked for volunteers to act in a play and I found myself on that platform, I knew that here on stage was a safe place for me. Now I wonder how many more Wednesday afternoons at 4.45 I can take, when my guests from the matinee have gone and I am stuck in my box on Eighth Avenue until it’s time to prepare for the evening performance. There are so many other ways of spending my time and I don’t want to miss out.”

After the success of his book Dropped Names, a memoir of the many famous people he has met over the years, Langella is writing a sequel. What conclusions has he reached on the nature of fame?

“Fame is fleeting, awards and titles are fleeting, joy and pain are fleeting and life has a way of slipping away from you. I quote George Bernard Shaw. ‘Stick to your soul’, he says, ‘that’s all we can do’.”

King Lear, Minerva Theatre, Chichester, until Sat 30 Nov 2013, Box office 01243 781312 www.cft.org.uk

Words: Al Senter