On the grapevine: A riesling to be happy

Wine expertise from Stephen Quinn

Chance sometimes introduces us to wines in ways that make life seem extraordinary. While in Berlin recently I dined with a group of friends at an ordinary Turkish café. Late in the evening I discovered a wine rack at the back of the room.

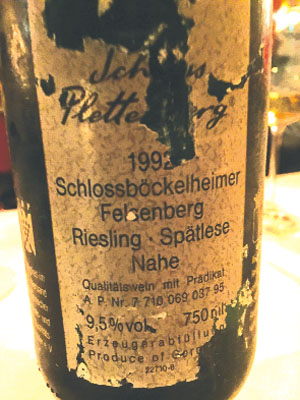

The café owner, Mehmet, only spoke German and Turkish. But we negotiated a rate of 20 euros a bottle. Apparently, the wines had been there when he bought the lease about 15 years ago. Most of the wines had no labels, or the labels were so damaged they were difficult to read. The only hint was the bottle; the long, thin shape meant they had to be rieslings. These wines must have endured years of temperature fluctuations from below zero in Berlin’s winter to more than 40C in summer. These kinds of fluctuations are bad news for wine, and the damaged labels proved the wines had been stored badly. This leads us to reflect on the wonder of German riesling.

All wines offered extraordinary mouthfeel, like kissing angels

These whites are often consumed young, when they offer fruity and aromatic wines with flavours of green apple, grapefruit, gooseberry, rose blossom or cut green grass. They taste crisp because of the high acidity. Yet this acidity, if combined with quality fruit, produces rieslings with exceptional potential for ageing. Quality dry riesling can be enjoyed half a century after bottling. High sugar content provides an extra preservative, making sweeter wines especially suited for cellaring.

Riesling is seldom oaked and is highly expressive of its terroir, meaning that the character is influenced by the wine’s place of origin. The grape variety orginated somewhere in the valley of the Rhine, since both its genetic parents, Heunisch and Traminer, have a long documented history in Germany. A third of all Germany’s riesling grows in the Mosel Valley but the Pfalz, Nahe, Rheinhessen and Rheingau regions also produce wines of substantial quality.

We opened four wines at the table and three were acutely memorable. Mehmet tipped the fourth down the sink. In order of discovery, from the crowded racks we drank a 1992 Schlossbockelheimer Felsenberg spatlese from Schloss Plettenberg in the Nahe region, a 1997 Durkheimer Feuerberg Kerner auslase from Pfalz, and finally a 1996 Kreuznacher Hofgarten Huxelrebe auslase from the Reichsgraf von Plettenberg vineyard in Nahe.

All had low alcohol, of about 9 or 10 per cent, and had been stored poorly. The labels were barely readable.

Yet the corks were in good condition and the aromas sublime – a range of fruit flavours like ripe apricots, mango and pineapple combined to give a sensation of sunshine and joy in the mouth. The kerosene notes were mere hints in the background, like sweet memories. More pronounced were the aromas of honey and syrup, like the smell of toast lathered with honey at breakfast. All wines glistened a golden colour in the glass, and offered extraordinary mouthfeel, like kissing angels. The people at my table smiled in silence, reflecting on the joys of being alive.