Film: Poetry or propaganda?

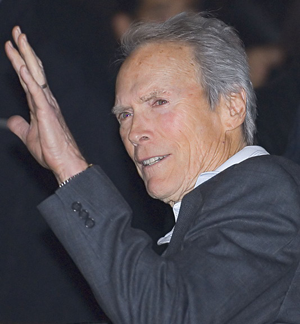

Last week I wrote about American Sniper and I just couldn’t help but do so again, although that isn’t quite the compliment it sounds … 2014 might have been a failure for Clint Eastwood, after his blunder with the big-screen version of musical Jersey Boys the past summer, until he released a surprise into the Oscar season (that’s pre-Christmas in America although it is out in cinemas of the UK now); American Sniper, the Iraq War drama starring Bradley Cooper as the most lethal sniper the US military has ever employed. The previous most notable time Eastwood snuck a movie into December at the last minute it was Million Dollar Baby, the eventual Best Picture winner.

I love Million Dollar Baby as a film – it’s tender, the performances are evolved and although its final sequence gives us a poignant, albeit limited, treatment of the topic of euthanasia, the film’s lack of interest in the ethical and legal details of modern medicine give it a dreamlike quality as the ethical and legal details are brushed over. That makes it a great piece of filmmaking. The issues within the film I’m not so behind: Million Dollar Baby was controversial because to some viewers it conveyed an unfortunate view of disability, suggesting that life with a disability might not be worth living. Eastwood’s character is seen as good and heroic for euthanizing his disabled friend.

Equally, American Sniper brushes over many ethical issues raised by its protagonist’s line of work. But it is a shrewder piece – a focused declaration that Eastwood owns the ‘war film’. Right from its taught opening scene we can marvel at the direction; at its poise and subtlety, at the handling of Bradley Cooper’s huge acting ability (which, in all honesty, I personally hadn’t felt before this film) and at the raw honesty of the bloodiness of war.

Yet, it is a bloodshed felt emotionally only on one side. When Iraqis die there are no meaningful moments, no powerful pauses, no care is given. I often wonder, when actors take a role that boils down to ‘malevolent, deceitful native’ do they do so believing that elsewhere in the film are positive representations of people from their culture? A thought along the lines of “it’s okay; I’m just characterising the one percent of bad people”? Sadly not in this film.

Here the Iraq occupation is seen through the sight of a high-powered rifle belonging to the man who wrote the memoir this film is based upon: Chris Kyle, a man who, thanks to an unprecedented number of sniper kills, earned the sobriquet “the Legend”.

Kyle may have felt that his enemies represented a “savage, despicable evil” (as he wrote in his book) but that gives Eastwood no right to make what is essentially a propaganda film.

Follow me: @latestjessica